…

Trapped within Earth’s permafrost – ground that remains frozen for a minimum of two years – are untold quantities of greenhouse gases, microbes, and chemicals, including the now-banned pesticide DDT. As the planet warms, permafrost is thawing at an increasing rate, and scientists face a host of uncertainties when trying to determine the potential effects of the thaw.

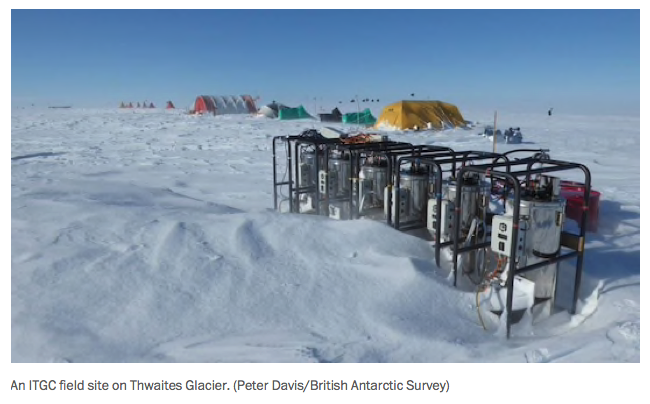

A paper published earlier this year in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment looked at the current state of permafrost research. Along with highlighting conclusions about permafrost thaw, the paper focuses on how researchers are seeking to address the questions surrounding it.

Infrastructure is already affected: Thawing permafrost has led to giant sinkholes, slumping telephone poles, damaged roads and runways, and toppled trees. More difficult to see is what has been trapped in permafrost’s mix of soil, ice, and dead organic matter. Research has looked at how chemicals like DDT and microbes – some of which have been frozen for thousands, if not millions, of years – could be released from thawing permafrost.